Page 1

Page 3

902601

John Marshall

The law, Marshall writes, “is the profession which more than any other

lends to independence & to fame. Almost all the eminent men of our country are lawyers.”

John Marshall, 1755-1835. Delegate to the Constitutional Convention, 1788; Secretary of State, 1800-1801; Chief Justice of the United States, 1801-1835. Outstanding content Autograph Letter Signed, J Marshall, as Chief Justice, three pages, with integral leaf, 6" x 8¾", Richmond, [Virginia], April 10, [1820].

The most influential Chief Justice in American history writes to his nephew, Martin P. Marshall, who was then practicing law in Cincinnati, Ohio, at age 22. He encourages him in the law: ”I am glad to hear that your situation in Cincinnati is so eligible. It will require time & assiduous attention to establish yourself anywhere in your profession; but, when once established, it is the profession which more than any other lends to independence & to fame. Almost all the eminent men of our country are lawyers.”

This warm, chatty letter from an uncle to his nephew is quite different from Marshall's more routine letters discussing legal matters. This letter contains some law: discussions of family real estate and of Marshall’s concern over a pending lawsuit in which he apparently was involved and hoped that ”the court will be favorable.” But there is also much more. Marshall mentions having been in Washington, D.C., where indeed as Chief Justice he had delivered opinions in eight cases between March 8 and March 17, 1820. He also congratulates his nephew on his marriage, writes of family, and, as noted, encourages him in his law practice. He writes:

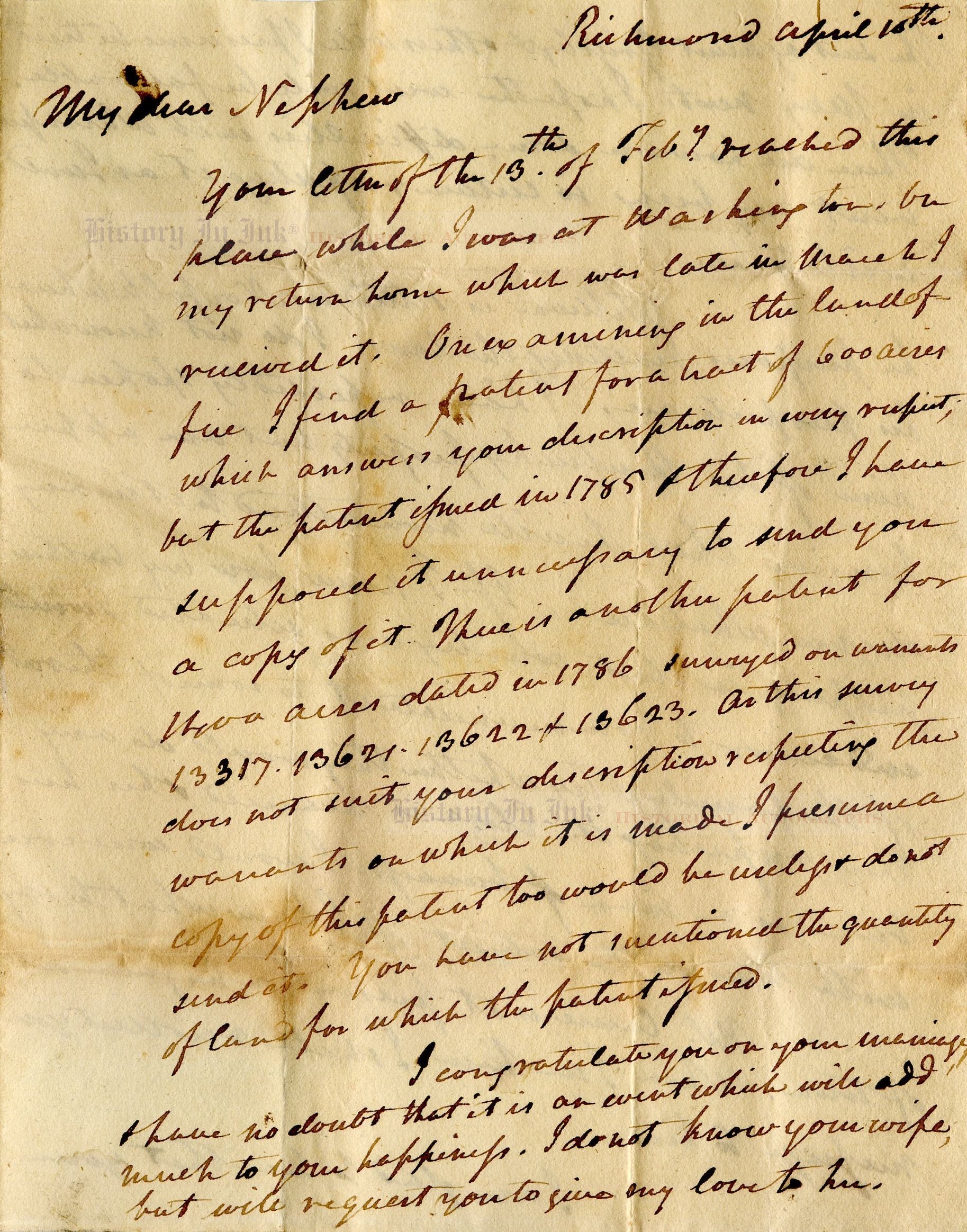

My dear Nephew

Your letter of the 13th of Feby reached this place while I was at Washington. On my return home which was late in March I received it. On examining in the land office I find a patent for a tract of 600 acres which answers your description in every respect, but the patent issued in 1785 & therefore I have supposed it unnecessary to send you a copy of it. There is another patent for 1400 acres dated in 1786 surveyed on warrants . . . . As this survey does not suit your description respecting the warrants on which it is made I presume a copy of the patent too would be useless & do not send it. You have not mentioned the quantity of land for which the patent issued.

I congratulate you on your marriage, & have no doubt that it is an event which will add much to your happiness. I do not know your wife, but will request you to give my love to her.

The suit against Grigsby & others will I presume be tried in May next. I hope the court will be favorable. There are however some difficulties in it which prevent my being so certain respecting it as I could wish to be.

William is settled in Norfolk where he purposes practicing the law. I do not know what his prospects are. I have repeatedly spoken to him of his Kentucky property but am apprehensive that he will never attend to it in any degree whatsoever. If I knew how my brothers [sic] property in that country was situated I would endeavor to communicate it to some of the rest of the family & try whether they would do anything respecting it. Eliza is married & her husband is a man of business. I would converse with him on the subject if I knew what to say.

Mr. Currie is at present on his farm out of town. When I see him I shall recollect your message to him.

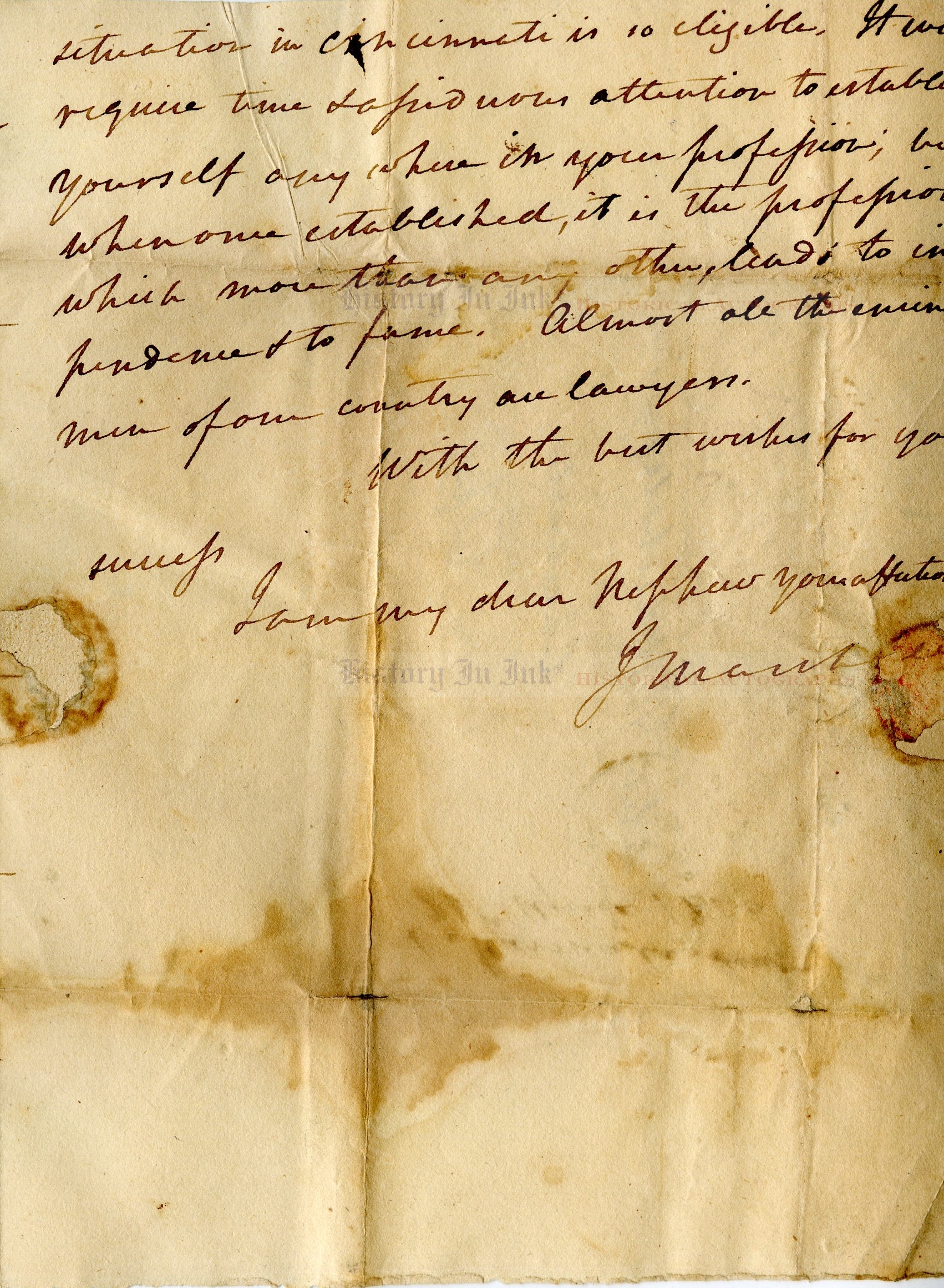

I am glad to hear that your situation in Cincinnati is so eligible. It will require time & assiduous attention to establish yourself anywhere in your profession; but, when once established, it is the profession which more than any other lends to independence & to fame. Almost all the eminent men of our country are lawyers.

With the best wishes for your success

I am my dear Nephew your affectionate

J Marsh[a]ll

Martin Pickett Marshall (1798-1883), to whom this letter was written, was the son of John Marshall's younger brother, Charles. When Charles died in 1805, the Chief Justice took the 7-year-old Martin to live with him and his family in Richmond, Virginia. Martin remained there several years, reading history and philosophy, and thus was as much a son to John Marshall as he was a nephew.

Martin moved to Kentucky in 1816, where other Marshall family members lived. He studied law under another of Chief Justice Marshall's brothers, Alexander K. Marshall, and was licensed to practice law in 1818. Interestingly, he then married his cousin, Eliza Colston Marshall, the daughter of yet another of Chief Justice Marshall's brothers, Thomas, and his second wife. Thomas lived in Kentucky as well—which explains why the Chief Justice did not know his niece, Martin's wife, but asked that Martin nevertheless give her his love.

Martin moved to Cincinnati after his marriage and practiced law there 11 months before returning to Kentucky for health reasons. He was known as a great student, with a “well selected" library, and a natural orator. He ultimately became prosecuting attorney, state representative, state senator, and a four-time presidential elector, twice for his close friend Senator Henry Clay. Although Martin was a slave owner—one contemporary writer noted that he lived in "very fine" style and that "every one of his children is waited on at breakfast, dinner &c. by a little slave"—he opposed secession and was a strong supporter of the Union during the Civil War.

Although Chief Justice Marshall did not mention that he himself was one of “the eminent men of our country" who were lawyers, his influence on the development of American constitutional law, and thus on the American system of government itself, was immense. Marshall served for more than 34 years, participated in more than 1,000 decisions, and wrote more than 500 opinions. It was his opinion in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), that established the authority of the judiciary to review the constitutionality of laws enacted by Congress. “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department,” Marshall wrote, “to say what the law is." In Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. 264 (1821), Marshall established the Supreme Court's jurisdiction to review the criminal decisions of state supreme courts, an extension of the Court's ruling in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, 14 U.S. 304 (1816), that it had supremacy over state supreme courts in state cases involving federal constitutional questions. In McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316 (1819), Marshall established that the states could not impede the constitutional exercise of power by the federal government, and in Gibbons v. Ogden, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824), he invalidated a state law on the ground that it conflicted with the right of Congress constitutional power to regulate interstate commerce. In short, much of the basic constitutional framework under which the United States functions today is the Constitution as John Marshall interpreted it.

Marshall contemplated several offers to serve in the Washington and Adams administrations. He declined service as attorney general for Washington; he declined positions on the Supreme Court and as secretary of war under Adams. At Washington's direction, Marshall ran successfully for a seat in the United States House of Representatives, but his tenure there was brief. Adams offered Marshall the position of Secretary of State, which Marshall accepted. When Oliver Ellsworth resigned as Chief Justice, Adams turned to the first Chief Justice, John Jay, who declined, and then opted for Marshall. Marshall continued to serve as Secretary of State through the remaining two months of Adams' term.

We have found only four letters by Marshall to family members in auction records since 1975. We cannot find that this letter, a part of Marshall family correspondence that we have acquired, has ever been on the autograph market before.

Marshall's signature on this letter was positioned directly under the wax seal on the other side of the paper, and the last three letters, "all,” were damaged when the letter was opened. The letter has been professionally repaired, however, so all of the letters except the "a" in the last name are there. The rest of the handwriting is bold. The letter has normal mailing folds; some creases and stains, as the scans below show, that are not uncommon for a piece this old; repaired paper loss where the wax seal, no longer present, was located; and a few tiny fold splits, slightly affecting a couple of words, which we mention for the sake of accuracy. Overall the letter is in fair to good condition, and we would say that it is very good were it not for the tear affecting part of the signature.

This is a desirable and uncommon example of Marshall's holograph and one that belongs in the finest Supreme Court or legal collection.

Unframed.

_____________

This item has been sold, but

click here to see other

Supreme Court items

that we are offering.